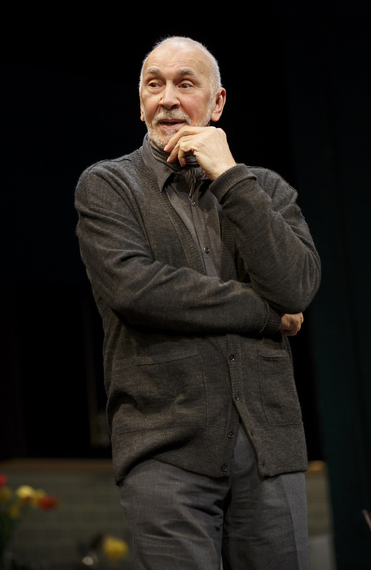

Frank Langella in The Father.

Photo: Joan Marcus

Frank Langella, at his estimable best, is not to be overlooked. Here he is, once more, in the Manhattan Theatre Club production of Florian Zeller's The Father. At his best, yet again, and not to be missed.

Langella is a rarity among American actors of his generation (he was born in 1938, making his Broadway debut in 1966). While he has numerable film and television credits, he has chosen to concentrate his career on the stage. He gave an arrestingly original performance in 1975 in Seascape, playing an Edward Albee lizard (of all things) and winning his first of three Tony Awards thus far. He was subsequently seductively droll in the smash 1977 revival of Dracula; lauded in Strindberg's The Father (unrelated to this new play) and Turgenev's Fortune's Fool; and mesmerizingly commanding as our most reviled president in Frost/Nixon in London (2006), New York (2007) and on screen (2008).

Langella keeps astonishing; and the passing years--he is now 78--only seem to deepen his power to draw us in and make us feel. In The Father, he adds something new to his well-honed arsenal of actorly skills. After lulling us into thinking, over the first hour of this ninety-minute play, that this is just another one of those excellent failing-old-men performances, the ground slips from under him (and us)--at which point the actor, and his audience, feel an altogether new kind of terror.

André (Langella), a retired engineer, has reached the point where he can no longer take care of himself; a man of stubborn determination, he vehemently ignores the uncompromisingly approaching shadow. His sparring partner is daughter Anne (Kathryn Erbe), who--as the play opens--is arranging to move from Paris to London; thus, an attendant has to be hired to look after The Father. (He apparently assaulted the last one with a curtain rod, and we can easily believe it.) The illness progresses in by-now-familiar stages, as the protagonist sinks into dementia and what Wm. Shakespeare used to call "second childhood." But this André won't go without putting up a fight, and in Langella's hands it's quite a fight.

Zeller--a widely popular French playwright and novelist--is not content with standard treatment here. We are accustomed to watching the patient gradually misunderstand, misconstrue and altogether miss what is being said by the other characters. Thus, we-the-audience take said other characters at their word. As The Father progresses, we realize that we are not hearing what is being said to André; we are hearing what he is hearing, seeing what he thinks he is seeing. As the play swiftly races by, we start to realize just how much--or how little--André comprehends, because the playwright has put us in his carpet slippers. Not only is the plot information suspect, along with the staging and even the scenery; the characters themselves are suspect, leaving the audience to question what has been presented on stage--which is, of course, a reflection of André's predicament. As a well-trained audience, we only know what we're told; in this case, the playwright appears to be feeding us the same alternate reality that André is struggling through.

(The Father--which originated in Paris in 2012--has been deftly translated by British playwright Christopher Hampton, author of The Philanthropist and Les Liaisons Dangereuses, and enjoyed a successful West End production last fall. The Manhattan Theatre Club production uses an altogether different cast and creative team. It is worth noting that while the title page of the Playbill is noncommittal, the Zeller-Hampton script labels the play as a tragic farce.)

Frank Langella and Kathryn Erbe in The Father.

Photo: Joan Marcus

Long-time Langella watchers, prepped on the subject of the play, might walk in with an idea of what to expect from the actor. The courtly charm in which he'll cloak his irascibility; the off-center sidestepping he will employ, pretending his character understands when he and we know he does not; the bluster, the overfriendliness, the harsh cruelty, the ploys for sympathy, the breaking down as his world (and his sense) slip away. What makes this performance so remarkable, though, is that Langella reaches a chasm where all those tricks--which André-the-character would likely employ, and Frank the actor would surely employ--are played out.

At this point, we are left with pure, harrowing terror: the mask is thoroughly removed, and the character stands naked as he stares into the abyss. And it is at this point that Langella surpasses himself. His Lear (at the Chichester Festival in 2013 and BAM in 2014) was equally harrowing, yes; but there he was playing an ancient king in a mythical world. Here, he is an average man--a father--of today. Thus, he might as well be you or me, our parent or grandparent. As André begins his final departure from rational understanding, Frank--who regularly carries a grand flourish, onstage and off--is left bare and unsupported, crawling and clinging to the stage of the Friedman. Langella outdoes himself, making this a theatrical feat to experience and to feel.

Kathryn Erbe, from stage, screen and television, acquits herself well as the daughter; so do four others playing multiple roles, with Hannah Cabell standing out (perhaps because she is favored with the most sympathetic writing). MTC regular Doug Hughes (Doubt) does a good job of staging this alternate reality, with an especially nifty assist from set designer Scott Pask. Pask has done wizardly work on items like The Book of Mormon, Something Rotten! and The Pillowman. Here, the scenery plays tricks--sly at first, like a lighting stanchion that moves from one wall panel to another--which keep Langella and the audience off balance. Donald Holder's lighting is effective as well, although the use of extra-bright flashing lights during scene changes might be physically uncomfortable for some patrons. (Do that once or twice to signal the character's disconnect, and that's fine; do it again and again and again and again, and it might become an overused device more annoying than theatrical.)

Hannah Cabell and Frank Langella in The Father.

Photo: Joan Marcus

After all is said and done, though, you have Zeller's provocative new play--already an international crowd-pleaser--and a monumental turn from the star. Hughes provides effective staging, but by this point in time one wonders whether directors have learned to simply step aside and watch Frank go.

.

The Manhattan Theatre Club production of Christopher Hampton's translation of Florian Zeller's The Father opened April 14, 2016 and continues through June 12 at the Samuel J. Friedman Theatre